The New York Times Health section posted an article on a debatable topic concerning three women in Florida who underwent stem cell intraocular injections which led them to go blind. Stem cells from one’s own body are not considered a drug so have little FDA oversight and while the use can powerful in the therapeutic process, further clinical research needs to be conducted for safe effective use.

Patients Lose Sight After Stem Cells Are Injected Into Their Eyes

By DENISE GRADY

MARCH 15, 2017

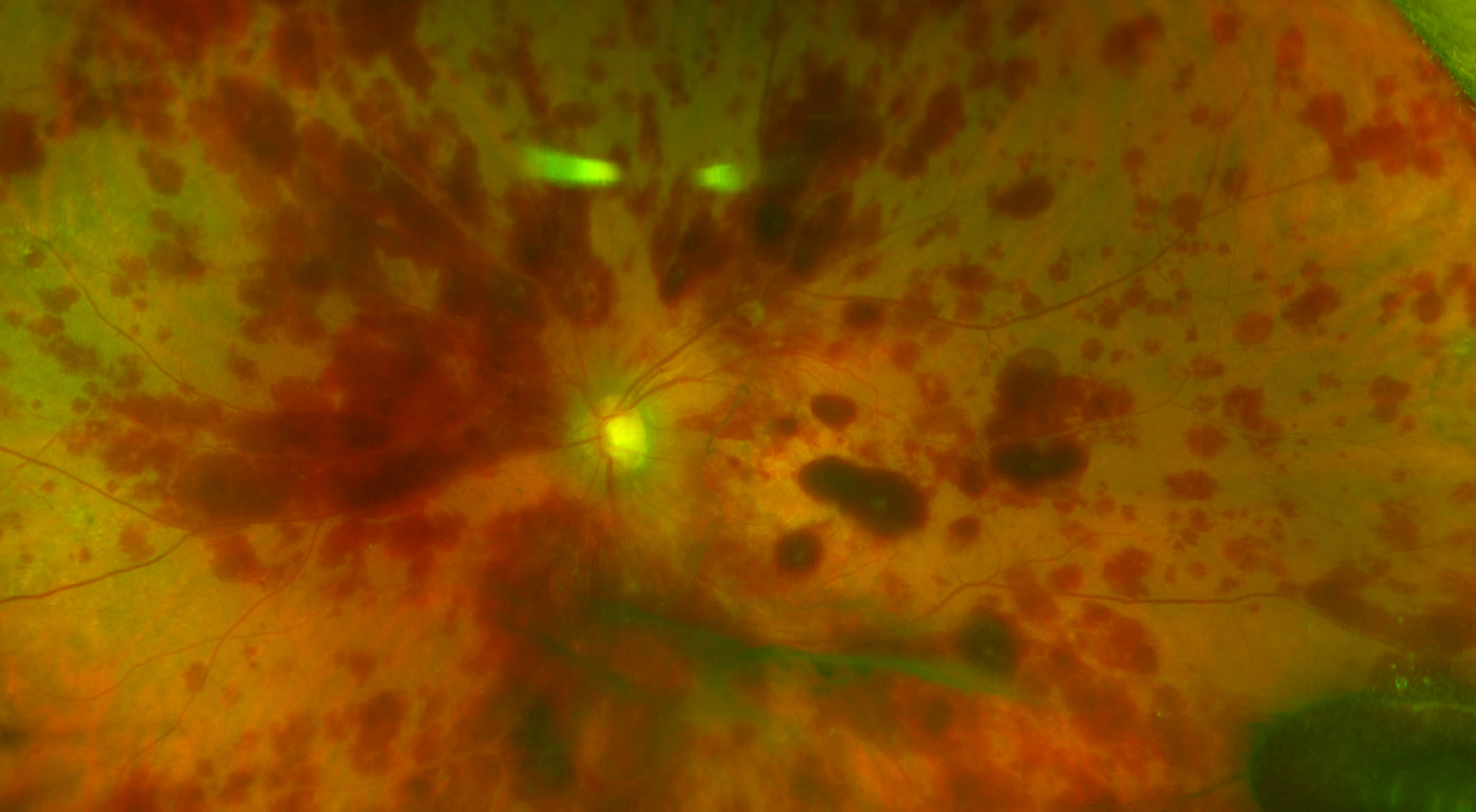

Credit: Dr. Thomas Albini

Three women suffered severe, permanent eye damage after stem cells were injected into their eyes, in an unproven treatment at a loosely regulated clinic in Florida, doctors reported in an article published Wednesday in The New England Journal of Medicine.

One, 72, went completely blind from the injections, and the others, 78 and 88, lost much of their eyesight. Before the procedure, all had some visual impairment but could see well enough to drive.

The cases expose gaps in the ability of government health agencies to protect consumers from unproven treatments offered by entrepreneurs who promote the supposed healing power of stem cells.

The women had macular degeneration, an eye disease that causes vision loss, and they paid $5,000 each to receive stem-cell injections in 2015 at a private clinic in Sunrise, Fla. The clinic was part of a company then called Bioheart, now called U.S. Stem Cell. Staff members there used liposuction to suck fat out of the women’s bellies, and then extracted stem cells from the fat to inject into the women’s eyes.

The disastrous results were described in detail in the journal article, by doctors who were not connected to U.S. Stem Cell and treated the patients within days of the injections. An accompanying article by scientists from the Food and Drug Administration warned that stem cells from fat “are being used in practice on the basis of minimal clinical evidence of safety or efficacy, sometimes with the claims that they constitute revolutionary treatments for various conditions.”

Kristin C. Comella, the chief science officer of U.S. Stem Cell, said in an interview that the clinic did not need F.D.A. approval because it was treating patients with their own cells, which are not a drug. She said the stem-cell treatments were comparable to patients’ receiving grafts of their own skin — a procedure not a drug.

Two of the eye patients sued the clinic and settled, but it has faced no other penalties. Ms. Comella said it no longer treats eyes, but continues to treat five to 20 patients a week for other problems like torn knee cartilage and degenerating spinal discs.

All three women found U.S. Stem Cell because it had listed a study on a government website, clinicaltrials.gov — provided by the National Institutes of Health. Two later told doctors they thought they were participating in government-approved research. But no study ever took place, and the proposed study on the site had no government endorsement. Clinical trials do not need government approval to be listed on the website.

Legitimate research rarely, if ever, charges patients to participate, scientists say, so the fees should have been a red flag. But many people do not know that.

Promising stem-cell research in eye disease and other conditions is taking place. But researchers and health officials have been warning for years that patients are at risk from hundreds of private clinics that have sprung up around the United States and overseas, offering stem-cell treatments for all manner of ailments, like injured knees, damaged spinal discs, neurological diseases and heart failure. Businesses promising “regenerative medicine” have multiplied, with little or no regulation.

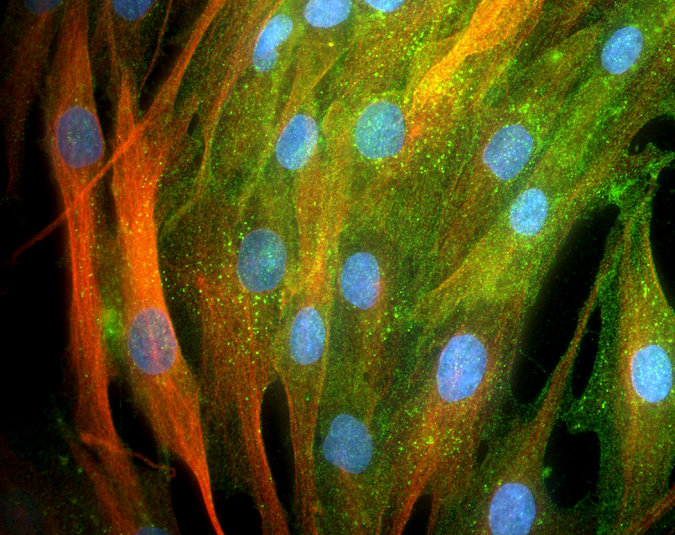

Credit: Scott McIntyre for The New York Times

Stem cells, which can develop into many different types of cells, are thought to have tremendous potential to repair or replace tissue damaged by disease, injury or aging. But so far, the F.D.A. has approved only a few stem-cell products to treat certain blood disorders.

The women in Florida suffered detached retinas, in which the thin layer of light-sensing cells that send signals to the optic nerve pulls away from the back of the eye — a condition that usually needs prompt surgery to prevent blindness. Doctors who examined the patients said they suspected that the stem cells had grown onto the retina and then contracted, pulling it off the eyeball.

One woman had such high pressure inside her eyes — about three times the normal level — that it may have damaged her optic nerves. Doctors operated quickly to relieve the pressure, but she became blind.

“The really horrible thing about this is that you would never, nobody practicing good medicine would ever do an experimental procedure on a patient on both eyes on the same day,” said Dr. Thomas A. Albini, an author of the article who saw two of the patients, at the Bascom Palmer Eye Institute at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine.

Standard practice, he said, is to treat one eye at a time, usually the worse eye first, so that if something goes wrong at least the patient still has one eye left with some vision.

Dr. Albini said his team alerted the F.D.A. after the second patient showed up.

“They did send an investigator who took statements from us,” he said. “They apparently wrote up a report, which as far as I know is still not finished or available for public consumption.”

Andrea Fischer, a spokeswoman for the F.D.A. said the agency could not comment on whether an investigation had been conducted.

Two of the women were not available for interviews because their lawsuit settlements in 2016 included nondisclosure agreements, according to their lawyer, Andrew B. Yaffa, of Coral Gables, Fla. He also was barred from discussing the case, but a publicly available complaint he filed in July 2016 details one patient’s story, and states that the injections were performed by a nurse practitioner who was introduced as a physician.

The third patient did not sue, but did not respond to a request for an interview made through her doctor. (The patients were not named in the journal article.)

Ms. Comella, from U.S. Stem Cell, said that an independent review board had approved the proposed eye study, including the plan to treat both eyes at once. She said a total of three patients ever received eye injections at the clinic, and were not part of a trial. She declined to confirm that they were the same three patients described in the journal article, but the article links the women to the clinic.

Credit: Riccardo Cassiani-Ingoni/Science Source

Ms. Comella said a trial never did begin, because the first three cases “ended the way they ended, so we decided not to go forward with any additional patients.”

She declined to discuss the cases further, citing the nondisclosure agreement. But she said that U.S. Stem Cell had successfully treated thousands of patients for other conditions, and that it was misleading to draw attention to “a handful of adverse events.”

U.S. Stem Cell also makes money by training doctors to extract stem cells from fat. And in a blog post on Tuesday its chief executive, Mike Tomás, said the company expected to open clinics throughout the Middle East, in Kuwait, Dubai and Qatar.

But the company, which is a penny stock, is struggling financially, and as recently as last fall warned investors that its poor financial situation put it at risk of going out of business.

Clinics like U.S. Stem Cell that extract stem cells from fat fall into a gray zone. Regulations say stem cells do not have to be F.D.A. approved if they are the patient’s own and are “minimally manipulated” — but some clinics may stretch that term to suit their own purposes.

The F.D.A. website has a page that warns “the hope that patients have for cures not yet available may leave them vulnerable to unscrupulous providers of stem-cell treatments that are illegal and potentially harmful.”

The F.D.A. article in The New England Journal of Medicine suggested that adverse events from stem-cell treatments “are probably much more common than is appreciated, because there is no reporting requirement when these therapies are administered outside clinical investigations.”

Like the Florida patients, people who consult clinicaltrials.gov may assume that the studies listed there have been approved by the F.D.A. or the National Institutes of Health, but that is not necessarily the case, Renate Myles, an N.I.H. spokeswoman, said.

In an email, Ms. Myles said, “The information on ClinicalTrials.gov is provided by the study sponsor or principal investigator and posting on ClinicalTrials.gov does not necessarily reflect endorsement by the N.I.H. ClinicalTrials.gov does not independently verify the scientific validity or relevance of the trial itself beyond a limited quality control review.”

Ms. Myles said that the site urges patients to consult their own doctors about joining studies and includes caveats in multiple places.

“However, we agree that such caveats need to be clearer to all users and will be adding a more prominent disclaimer in the near future,” she added.

A version of this article appears in print on March 16, 2017, on Page A16 of the New York edition with the headline: After Stem Cell Shots in Their Eyes, 3 Patients in Florida Lose Vision.

Link to article: https://nyti.ms/2mKl9zp